Bolivia comes up with the next somewhat controversial item on the program. We drive our campervan Ben to Potosí, the historic silver capital of the world. We want to learn about the history of silver in connection with Potosí. Not only can we visit a museum, but we can also experience first-hand how silver was mined in Potosí and still is today. We spend two exciting days in Potosí.

History of silver mining in Potosí

The city of Potosí was founded at the foot of Cerro Rico, which translates as “rich mountain”. Even before the Spanish colonialists invaded South America, silver was mined on Cerro Rico by the Incas. At that time, the deposits were so rich that there was enough silver ore on the surface of the mountain to meet the needs of the Incas. However, the Incas used the silver primarily as jewelry and less as a valuable precious metal or money. The situation changed abruptly when the Spanish began to extract the silver from Cerro Rico from various mines on a large scale. This change happened in the 16th century. Potosí quickly became the most important source of silver for the Spanish Empire and became world famous as a result. A mint was also established in Potosí, which cemented its strong position as the Spanish empire’s largest silver mine in the historical world.

The downside of this wealth was, of course, the impact on the local population. Many workers were forced to work in inhumane conditions either in the silver mines or in the mint. In many cases, literally until they dropped respectively died prematurely.

In more modern history, the Spaniards were replaced by the local government as exploiters of the silver and tin deposits. For the workers, the precarious working conditions changed very little, which ultimately led to a violent uprising by the population against the incumbent president. As a result, the mines came into the hands of local mining cooperatives, which regulate mining among themselves and ensure that the miners benefit from a larger share of the added value. These mining cooperatives are still active today and regulate the extraction of the various valuable materials from Cerro Rico. Some of these mines can now be visited during normal operations.

Although the miners now earn better wages, the working conditions are extremely poor and the long-term consequences grave. A large number of workers die in accidents in the mines every year; by the time of our visit at the end of September, 80 people had already died in 2024, and life expectancy is also very poor due to long-term effects. In addition to men and women, children also work in the mines! Officially, they are allowed to enter the mines from the age of 16, but unofficially, many miners’ children work in the mines as their parents’ assistants from the age of 12 or even younger.

Mine tour in Cerro Rico

At first, we are not sure whether we should take part in a tour of the mines in Cerro Rico or not. Although mining is regulated by local cooperatives, we think the conditions in the mines are very bad. Since the last clash between the miners and the government, the government has stayed completely away from Cerro Rico. It is a lawless area, so to speak. This is reflected in many facets. We ask ourselves whether we want to support such a double-edged issue through our tourism or whether we should skip Cerro Rico and its silver mines. It is also important to know that the mine tour is carried out under normal mining operations. There are no additional safety measures just because uninformed tourists are walking around the mines. In the end, Paddy’s curiosity and thirst for adventure got the better of him. So, on a Monday, we book a tour of the silver mines in Cerro Rico.

With a helmet, simple protective clothing against the dust, rubber boots and a headlamp, we set off for Cerro Rico in a group of five. First stop: the mining supplies market. As in many Latin American cities, stores selling similar items are clustered in the same neighborhood. This is also the case at the mining supplies market. Everything a miner needs for his work is freely available here. It is important to note that few machines are used in Cerro Rico. Electric winches and pneumatic drills are the only higher technologies used. The main work is still done by dynamite, which is ignited with individual fuses. We are encouraged to buy gifts for the miners for our visit. And because Cerro Rico is the way it is, as tourists we can buy a stick of dynamite without a permit. Impressive – and we (or Paddy) are happy to take it with us for demonstration purposes. We also buy lemonade, water, coca leaves and 96% alcohol for the miners.

Even the mine entrance demonstrates how simple everything is here from a technological point of view. The ore from the mountain is obviously pushed out of the mountain by hand in small rail wagons and tipped outside into various loading stations. The loading stations for the trucks are simple heaps on the mountain which are separated by wooden planks. People then shovel the 20 tons of ore onto the trucks by hand and with wheelbarrows. After a brief welcome from two miners and their permission for us to visit the mine, we set off into the darkness of the finely branched tunnels in Cerro Rico. Our first mine is called Rosario and has probably been driven deeper and deeper into the mountain since colonial times in search of more silver, tin and other ores. Many of the beams supporting the mine tunnels make a dilapidated impression, some of them are already more than half collapsed. Well, the beams will probably last the 2 hours we spend in the mine if they have been preventing the mountain from collapsing into the tunnels for so long.

Unfortunately, maintenance work is underway on the day of our visit and we see the miners in the Rosario mine as a group at one point. Today they are installing a new wooden post to provide better support for the tunnel. On our tour we get deeper and deeper into the mountain, the surroundings change noticeably even without light. It gets warmer, dustier and finally even narrower. We change tunnels deep in the mountain to get a feel for a miner’s working day. We crawl and slide through a small side tunnel, diagonally downwards through the Cerro Rico. At this point, there is no room for walking either upright or bent over for around 60 meters. The only way to reach the Candelaria mine below is on all fours. The darkness, the dust and the constricting conditions are a psychological challenge. However, our guide Julio, a former minero, compensates for this with lively stories about everyday life in the mine. We make good progress through the second mine, Candelaria. Here, deep in the mountain, we see two miners pushing an ore wagon through the mountain. The workers are quickly replaced by us tourists and we help them push the wagon for a short distance. It is laborious, the wagon often derails from the sloping rails. And the wagon is not even filled with ore. The wagon weighs 500 kg empty, when full the smaller wagons weigh just over a ton, the large wagons can weigh up to two tons when full and are also only pushed out of the mountain by two miners.

Through Julio’s stories, we learn that many mineros start working in Cerro Rico at a young age as children. Officially, working in the mountain is only permitted from the age of 16. But without supervision, this rule is often disregarded. If the whole family only knows about mining work, the children from these families often have no other prospects. Accidents in the tunnels at Cerro Rico have also led to the sad fate of many orphaned children. Without education and family support, many of them have no choice but to go into the mines. At least the high risk is somewhat reflected in the wages. A worker in a mine in Potosí receives around three times a normal monthly salary. The better wages are of course a lure for many more workers to go into the mines day after day, despite the hard physical work and the dangers. For this reason, Bolivians with no prospects still come from all over the country to work in the mines around Potosí.

Our tour ends after 2 hours at the camp, where we return the equipment for the mine visit. But the quiet in the tunnels due to the maintenance work means that Paddy in particular is not really happy. Without further ado, another tour is booked for the next day in the most active mine in Cerro Rico, Caracoles.

Mine tour through Caracoles in Cerro Rico

The Caracoles mine is the most active mine in Cerro Rico. And according to Ariel, today’s guide, it is also the most active mine in the whole of Bolivia. Before the tour through Caracoles, the tour guide points out that you have to run in the tunnel. Namely to get to safety from the wagons carrying ore. The wagons have no effective brakes and the tourists are guests here and do not determine the pace of work. In contrast to the other two mines, Caracoles is very busy. Countless empty wagons are pushed into the mountain, and whenever full wagons come in the opposite direction, they are heaved out of the chutes to allow the heavier wagons to pass. And right in the middle, sometimes just a few centimeters away, we nestle up against the tunnel walls to avoid being hit by the wagons. In Caracoles, the rope hoists are in action to transport ore from lower-lying side tunnels to the wagons. They consist of unsecured vertical tunnels over several hundred meters and can be viewed at close range.

In the main tunnel, all the material for mining is also carried in and out. A team with air drills and accessories marches past us. In many places, the ore is loaded into the wagons from small side tunnels via simple wooden ramps. To get to the upper side of this loading station, we squeeze through a hole just the size of a man. A wheelbarrow is then used to transport the silver ore from further back in the mountain to the small loading station. Time to get to work. Paddy doesn’t have to be the first to break the ore out of the mountain, but his knowledge is more than enough to empty the full wheelbarrows. The two miners are available for a quick chat. They are happy with their wages, are working for about 9 hours today and will be back tomorrow. They are close to 30 years old and have probably adapted their lives to mining. The only thing they want is some sunshine at the end of their working day after the hours of darkness inside the mountain.

Casa de Moneda in Potosí

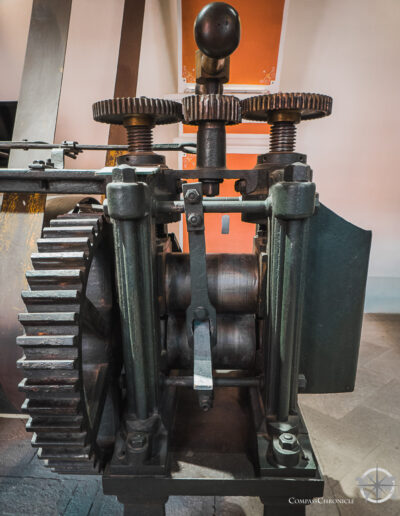

After mining the raw silver ore, we visit the Casa de Moneda in Potosí to get an impression of how the silver is refined. The former Spanish mint now houses a museum dedicated to the history of silver, mining and minting. The Potosí mint was one of the few in the whole of South and Central America. Silver ingots were first cast from the iron ore, which were then processed into smaller, flat ingots. These were rolled in special rolling machines to the thickness of the silver coins of around 2mm. The machines used for this were designed by Leonardo Davincci and brought from Europe to South America by the Spanish. Four mules were harnessed on the first floor, which provided the power to drive the rolling machines on the floor above. An ingenious mechanism made of wooden cogwheels can still be admired today in its original form. Very impressive!

In a next phase in the 19th century, the rolling machines were driven by stationary steam engines. And finally, at the beginning of the 20th century, the technology was upgraded to electric motors. However, the machines that punched and minted the coins remained largely identical. Only the energy source was changed. We really like the fact that the factory buildings have been faithfully preserved. We can almost feel the vibrations of the minting machines and rollers. The whole exhibition is easy to understand and can be experienced in a very authentic way. We highly recommend a visit to the Casa de Moneda in Potosí to learn about the processing of silver during the colonial era.

Old town of Potosí

The city center still has some old buildings from the colonial era. Especially around the main square and one or two alleyways around it, the buildings are still preserved in the old style and thus exude a pleasant charm. As soon as we move away from the city center, however, the appearance quickly changes to that of a poor industrial city. We can no longer speak of charm here; the rest of Potosí is very dusty, run-down and uninviting. We can’t blame anyone for this, it’s just the way it is: Potosí is a mining town at an inhospitable altitude of just under 4,000 meters.

0 Comments